|

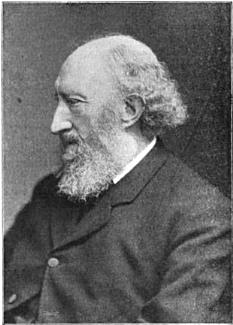

| Image source: Chambers Cyclopædia of Literature, London, 1903. Vol. III. p. 631. |

The appearance of the fourth volume of the new edition of the

History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate

marks the conclusion of the life

work of one of the great workers of the Victorian age. It is fifty years

since Samuel Rawson Gardiner first devoted himself to the study of the times

of the first Stewarts and of Cromwell. He lived to write the history of over

fifty years; the rate of his progress is, in some degree, the measure of the

thoroughness and exactness of his work; it took him well nigh as long to

discover the full truth about men's deeds as it did for the deeds to be done.

And no one who has read the many volumes in which he told the story will

accuse him of undue deliberation, still less of undue haste. He worked

continuously and surely, and it was a great result which he achieved.

As with most of the other eminent historians of the nineteenth century, the details of Gardiner's life mattered little to his work. It was not an eventful life: those who knew him cannot doubt that it was a happy one, but it was conspicuously a laborious life. There was never for him the possibility of devoting himself, without distraction, to historical research. During the fifty years he was at work on the great study of his life, and while he was spending all his spare hours in the British Museum, he was teaching also, and teaching often the most elementary subjects to mere beginners in historical studies. He had continually to undergo the strain, of which Bishop Stubbs spoke in one of his statutory public lectures, of having to turn from minute investigation of small points, building up the detailed history of a week or a month, to teaching on the elements of the same subject, broadly treated, and in a way that everyone could understand. Far rather would he turn, Dr. Stubbs said of himself, to a subject quite different, such as algebra or Euclid. And, indeed, he had theology to turn to. But to Gardiner no such variety was possible.

And Gardiner wrote a considerable number of little books. There is nothing

that Oxford scholars to-day are more laughed at for than their

little books.

It is said that their whole output is found in this

useless form of book-making. But it is well to remember that four of the

most eminent historians of the last generation, Green and Freeman, Gardiner

and Creighton, set the

example, and did not find such work incompatible with greater efforts.

One word, and one word only, need be said on the character of the man

himself; for, indeed, it was a prime factor in his success. He was the most

kind-hearted, modest, and generous of men. He welcomed good work wherever

he saw it. Close student though he was, he was nothing of a pedant. He had

a keen sense of humour, and a hearty width of friendliness which won him

welcome wherever he went. He was utterly destitute of self-consciousness;

he felt himself as happy as a junior fellow when he was old enough to be

father of his seniors—if the bull may be forgiven—as if he

were not one of the most famous scholars of Europe. Perhaps the personal

memories that will remain longest of him are those of kindly words of

encouragement and kindly words of fun. He enlivened the anxious and very

laborious work of the Honour examination in Modern History at Oxford by

many a quaint quip of speech. When examiners were compelled to set questions

on that marvellous piece of ponderous and ineffective dulness—dulness

which the sprightliness of the Oxford tutors who translated it was unable

wholly to conceal from the sagacity of those who studied it—Bluntschli's

Theory of the State,

Gardiner proposed to satisfy the obligation by

one comprehensive inquiry: Give your reasons for thinking Mr. Bluntschli

to have been an ass.

When the work of some candidates seemed to him to

be below even the lowest fourth class he described it in the word Fie!

and wrote it correspondingly in Greek, φ. But to any kind of good work he

was indulgent. He was eager to help young workers. He was appreciative of

their work, yet he never lowered, by praise which might be stimulating

though it were insincere, the high standard of historical presentation

which he set before his own eyes and those of his fellow-workers. He was

not one of those men of whom biographies are written. He will be remembered,

except by his friends, for his historical work alone.

In the case of no man would all who can judge more strongly deprecate

exaggerated language; and yet it must be said, how great his work was!

That we are now in a position to estimate it must be the excuse for this

article. We may well, when we think of Gardiner's History,

rub our

eyes, look around us, and see how far we have moved since he began to

write. He set himself fifty years ago to study afresh, like a great

constructive historian as he was—the phrase is that of Bishop

Stubbs—the most critical epoch in English history after the reign of

Henry VIII. He found, as everyone knows, the field occupied, for two

centuries past, by the most vehement and bitter partizanship. For generations

the Cavaliers had had their own way: Charles was a martyr, as the pulpits

proclaimed every year: Cromwell was a hypocrite and an usurper. Then came

the reaction, first of the Calf's Head Club, and then of the Whig historians.

The philosophic Conservatism of Hume yielded to the philosophic Whiggery of

Hallam and the fiery rhetoric of Macaulay. At last no name, of folly or

knavery, was too bad for Charles, or Laud, or Strafford. And then came the

rugged fervour of Thomas Carlyle, and the world was taught to believe that

Cromwell was incontestably right, and all his foes were villains, because it

was a matter of the eternal verities, and because all that the Cavaliers had

for their support was the pitiable protection of four surplices at

Allhallow tide.

In the days when Hallam and Forster and Carlyle ruled,

the Puritans swept the board.

And yet not without protest. A vigorous denunciation of Carlyle's philosophy,

of his idolatry of force, and of his toleration of guile, came from the pen

of James Mozley: it ended in a marvellous passage of trumpeted defiance in

which Cromwell's power was admitted, but as the power of a monster, and in

which the man himself stood forth from the gloom as a mighty beast. Wiser

and more truly critical were the three articles written in 1846 by Richard

William Church. He saw the greatness of the idea which Carlyle had before

his eyes. He saw the moral strength of Puritanism. But he accused the

hero-worshipper of an unreal tone of sentiment,

of the mistake of

forcing homebred English Puritans into full-blown divine heroes.

He saw how fine was the character of Cromwell as Carlyle imaged it—

the dim but unquestionable form of a genuine hero, with belief, veracity, valour, insight; strong in his hatred of falsehood, impurity, injustice, and stern in his way of quelling them,—genuine Englishman withal, rude and clumsy in speech, as Englishmen are.

But he thought that the reality did not answer to the vision. Thus he ended his survey of the great epic of Puritanism

—

And now we must take our leave of Mr. Carlyle we will do him this justice,—we believe that he meant to bring out a genuinely English idea of excellence, to portray a man of rude exterior and speech, doing great things in a commonplace and unromantic way. But we must match his ideal with something better than Cromwell's distorted and unreal character, his dreary and ferocious faith, his thinly veiled and mastering selfishness.

Such was the protest of a candid critic against the untempered eulogy of

Carlyle. It cannot be said to have received much, attention. The public

ear was caught by the great Whig writers, and they dictated historical

judgments for over a generation. Indeed, if one were to judge by the most

widely used school-books, it might be said that the Whiggish interpretation

of seventeenth century history triumphed absolutely, and triumphs still.

The example of Dr. Johnson, who would not let the Whig dogs have the

best of it,

had been turned in favour of the party he detested.

It cannot be said that Gardiner set to work to reverse this verdict. Certainly he had no such intention. His sympathies were with Liberalism rather than with Conservative principles. He detested absolutism in any form, and he was not enthusiastically or aggressively democratic. He had a traditional, a hereditary, admiration for Oliver Cromwell, from whom he was proud to trace descent. But much above these things was his transparent candour and his thorough sense of historic perspective. It was thus that, with no violence of reversal, a new view of the great men and the great crisis of the seventeenth century came into existence through his work. When this is said, it must not be forgotten that Leopold von Ranke, with a width of view and a philosophic power to which Gardiner had no claim, taught the truth about the seventeenth century in England as Gardiner taught it: perhaps even he saw it more completely because he stood farther away. But still, for Englishmen, and in detailed knowledge—where he far surpassed von Ranke—it was Gardiner who wrote the History of England from 1603 to 1655 as, for fact or opinion, it will never need to be written again.

What then was the way in which Gardiner taught men to reconsider the history

of the times with which he dealt? Everything, it may be said, depended on

the method: and the method was the method of the Oxford historians. Those who

have written lately on the work of this distinguished school have very

generally forgotten that Gardiner was a pioneer, not a disciple, among that

body. The first two volumes of his History

were published in 1863.

It was not until a year later that Stubbs edited his first volume for the

Rolls Series; and it was not till ten years later that the first volume of

his constitutional history appeared. Green did not write his first article

in the Saturday Review

till 1867, or publish the

Short History of the English People

till 1874. Freeman, it is true,

wrote with Basil Jones the History and Antiquities of St. David's in 1856;

but that was work of another type. The Clarendon Press did not begin to

issue the great History of the Norman Conquest

till 1867. Gardiner

thus was one of the first, if not the very first, to show on an extended

scale what the new method of historical study involved. At a time when by

the most modern of moderns Freeman has been discredited and Stubbs regarded

as antiquated, it may seem scarcely worth while to recall the revolution

in historical writing which these even effected. It may suffice to repeat

that they set the example of studying every known source of information

for the period on which they wrote; they for the first time showed the rich

stores of information which remained still in manuscript; they used their

authorities critically, as they had never been used before; they deliberately

set themselves to exclude the partisan view of history, which great writers

of their own time had striven to perpetuate. These were great services, and

Gardiner was among the foremost in rendering them.

What then did this method effect in the case of the seventeenth century?

To what extent did Gardiner succeed in forcing a reconsideration of that

great time of strife? It might be said in the first place, that it was in

innumerable details that the change was at first apparent. It was the

accuracy in minute points, the extraordinary patience of investigation,

where the search was not complete till all that it had discovered was taken

to the light, and turned this way and that, and weighed, and criticised, and

seen in relation to all other facts, important or insignificant, that were

in any way related to it, which men first observed in Gardiner's historical

work. Before he had proceeded far other writers came near to bettering his

instructions; yet, from the beginning to the end, in increasing minuteness

of care, no Englishman ever surpassed him. It would be possible to give

innumerable instances. Some will recall his personal investigation of

every site of importance with which he was concerned, his inspection of

battlefields and roads and fords; some will remember how, to the last, he

was finding new facts to illustrate a critical point, as in the discovery

of the plot which sealed the fall of Strafford. Some again will remember

how his keen interest in the geography of his subject was shown, for example,

when he was asking questions in viva voce at Oxford, by a reference

to the lie of the land

where events took place, to the harbour of

Cadiz, to the cellars of the Parliament house, or to those battlefields which

he had studied with the help of his bicycle and in the company of his wife,

as true a student as himself. His work was essentially accurate and minute.

But this minuteness was always subservient to, it never obscured, the main

issue. You always saw the wood itself clearly enough, for all the thick trees.

What then did Gardiner present as the solid results, new or confirmed,

of his minute investigations? Broad and salient characters and principles

can alone here be treated. Perhaps the first point which strikes the reader

is the treatment of the lesser worthies. The history of the Puritan

revolution is no longer the mere eulogy of Cromwell. Forster had spoken of

Eliot, and Browning of Pym, as men whose praise should be sounded among that

of the highest; but Gardiner came to show how closely their work was bound up

with the whole progress of the movement. Eliot was the foremost

political orator of his time.

His strength lay in the power of his

moral nature, in his extraordinary political enthusiasm and his abounding

faith in the greatness of Parliaments, the living mirror of the perpetual

wisdom of a mighty nation.

Side by side with the idealist was the

practical organiser of victory.

Pym was born to be a leader of men. He was not a philosopher like Bacon, with anticipations crowding upon his brain of a world which would not come into existence for generations. His mind teemed with the thoughts, the beliefs, the prejudices of his age. He was strong with the strength and weak with the weakness of the generation around him. But if his ideas were the ideas of ordinary men, he gave to them a brighter lustre as they passed through his calm and thoughtful intellect. Men learned to hang upon his lips with delight as they heard him converting their crudities into well-reasoned arguments. By listening to him they made the discovery that their own opinions—the result of passion or of unintelligent feeling—were better and wiser than they had ever dreamed. Nor was it by a mere dry intellectual logic that he touched his hearers. For if there is little trace in his speeches of that fertility of imagination which in a great orator charms and enthrals the most careless of listeners, they were all aglow with that sacred fire which changes the roughest ore into gold, which springs from the highest faith in the Divine laws by which earthly life is guided, and from the profoundest sense of man's duty to choose good and to eschew evil. Thus it came about that between this man and that great assembly a strong sympathy grew up—a sympathy which it has always refused to flashes of wisdom beyond its comprehension, but which it grants ungrudgingly to him who can lead it worthily by reflecting its thoughts with increased nobility of expression and by shaping to practical ends its fluctuating and unformed desires [History of England, 1603-1642, iv. 243-244.]

Gardiner in this fine passage was no doubt himself idealising; he forgot for the moment that Pym was a manager, an astute tactician, as well as an orator; but that he seized the secret of his power and expressed it to admiration who can doubt ?

So too he idealised the wisdom of Bacon. He saw it out of all relation to the practical needs of the time, and notably the religious difficulties. He perhaps followed Spedding too closely, for he had never quite the wisdom of insight possessed by Dean Church. But still he made men see what Bacon's political theories really involved, how wide they were, how far-sighted; and thus he set James's reign, as he set Charles's, in a new light. This was of course especially true through the view that he took of James himself. Macaulay had greedily followed in the errors of the gossips and the libellers: Green, later on, was never able to shake himself free of the infection. But Ranke saw the sagacity of James's ideas, the breadth of his foreign policy; and Gardiner, though, as an Englishman, he was less tolerant of its neglect of English opinion, did solid justice to the statesmanship of the king. The slobbering idiot with the passions of a brute disappears from history, and is replaced by a kindly, thoughtful, eccentric personage, many of whose schemes were wise and far-sighted, but whose incurable tactlessness, and the unhappy circumstances of the time, made them incapable of realisation.

As the volumes proceeded it was seen how, whatever partisans might have said,

even-handed justice was now meted out. Historical caricature had long made

the names of Buckingham, Strafford, Laud, its own—the reckless,

brainless favourite, the black apostate, the childish tyrant and bigot.

Men rubbed their eyes when they saw how the figures were changed in the

new light. Perhaps the greatest surprise was the new position won by

Buckingham. Even the students of history could not quite understand it;

but this, it must be said,, however respectfully, was due to their

ignorance. Even J. E. Green could not, he wrote, on his own facts

take Gardiner's estimate of Buckingham.

But the more they were looked

into, the more the facts showed that Gardiner's view was true. It became

impossible any longer to treat him as the mere favourite

—a

foolish word which has done as much as some other question-begging terms

to confuse English history. As it became clear that Buckingham had

principles, and even to some extent statesmanship, the simplicity of

Clarendon's judgment—in that as in so many things—had to be

laid aside. The more we read the more we saw that one who so deeply

influenced men of character so unlike as James and Charles, who

won—contrary to every natural anticipation—so warm a place in

the affection of the rigid ecclesiastic Laud—was a serious figure in

English history, a politician of impulse, but one who reasoned upon his

impulses, just one of those, in fact, who at all periods of the national

history have been most dangerous to the national stability. His was not

a simple character or a simple career, as men had thought. This is how in

the end Gardiner treated it.

The solution of the enigma is not to be found in the popular imagination of the day, and still less in the popular history which has been founded upon it. Buckingham owed his rise to his good looks, to his merry laugh and winning manners; but to compare him with Gaveston is as unfair as it would be to compare Charles with Edward II. As soon as his power was established, he aimed at being the director of the destinies of the State. Champion in turn of a war in the Palatinate, of a Spanish alliance, and of a breach first with Spain and then with France, he nourished a fixed desire to lead his country in the path in which for the time being he thought that she ought to walk. His abilities were above the average, and they were supported by that kind of patriotism which clings to a successful man when his objects are, in his own eyes, inseparable from the objects of his country. If, however, it is only just to class him amongst ministers rather than amongst favourites, he must rank amongst the most incapable ministers of this or of any other country. He had risen too fast in early life to make him conscious of difficulty i anything which he wished to do. He knew nothing of the need of living laborious days which is incumbent on those who hope to achieve permanent success. He thought that eminence in peace and war could be carried by storm. As one failure after another dashed to the ground his hopes, he could not see that he and his mode of action were the main causes of the mischief. Ever ready to engage in some stupendous undertaking, of which he had never measured the difficulties, he could not understand that to the world at large such conduct must seem entirely incomprehensible, and that when men saw his own fortunes prospering in the midst of national ruin and disgrace, they would come to the mistaken but natural conclusion that he cared everything for his own fortunes and nothing for the national honour [History of England, 1603-1641, vi. 358.]

With Strafford the new presentation was a vindication. Strongly though Gardiner's own opinions differed from those of Wentworth on every point, he followed the facts which he so carefully elicited till they shattered Macaulay's venomous absurdity of a great political apostasy, and set before him the picture of a man of deep and serious mind, a statesman who loved his country devotedly, and whose attachment to her ancient institutions, Church and Crown and Parliament, was almost a passion, a worker of extraordinary energy and of quite unselfish devotion, a chivalrous, sensitive spirit attuned to the highest aims. None the less Gardiner was relentless in showing the discord between Strafford's political theory and the practical facts no less than the imaginative needs of the seventeenth century. Progress, national responsibility, moral expansion, were perhaps impossible for England if Wentworth had prevailed; but Gardiner's picture must set men thinking whether they were any more possible under Cromwell.

With Laud the change was even more startling. Men had come to take it for

granted that here was a little man of little mind, a foolish person of

silly Romanist leanings, a very narrow, bitter, malicious creature. Even

now the notion lingers in school histories and in some religious

newspapers; not unnaturally, for Gardiner showed that Laud was more

tolerant than the Puritans. It may, perhaps, be said that if Gardiner had

studied Laud's works as closely as he studied Strafford's correspondence

or Cromwell's speeches he would have come nearer than he did to a complete

estimate of the remarkable man who, when he seemed to wreck the Church of

England, really preserved her less changed than any other national

institution through the wrack of the Civil Wars and the Interregnum. Laud,

Gardiner showed, was not a childish pedant, but a statesman with firm

opinions based upon the Anglican formularies, from which he never wavered

an hairsbreadth : he was a tolerant man, anxious to make room for diversity

of thought in the national Church; and his nobler aims were too much

in accordance with the needs of his age to be altogether baffled.

Those who sympathise with Laud's opinion will never feel that Gardiner did

them full justice, and they can point to passages in the Archbishop's own

writings which directly contradict the views which the historian attributed

to him. But they cannot fail to recognise that it was in the searching,

patient, judicial investigation of Gardiner that the important

historical rectification

of the last few years—as Mr. Gladstone

described it to the present writer—had its beginning. And his final

testimony must take rank among the permanent decisions of English history:

It is little that every parish church in this land still—two centuries and a half after the years in which he was at the height of power—presents a spectacle which realises his hopes. It is far more that his refusal to submit his mind to the dogmatism of Puritanism, and his appeal to the cultivated intelligence for the solution of religious problems, has received an ever-increasing response, even in regions in which his memory is devoted to contemptuous obloquy [History of the Great Civil War, ii. 108.]

Buckingham, Strafford, Laud were the three great historical restorations of

the earlier part of the history. But as the volumes were studied it seemed

as if all the well-known characters stood forth more really, less like

puppets, than they had ever done before. Charles I., like his father,

had something near justice done him. Gardiner subtly analysed his motives

and presented his actions very often in a new, sometimes in a more

favourable, light. But it was the minor characters most of all who came to

life again at his touch—the Gorings, Essex, Finch, Hamilton, Fairfax,

Lilburne, Prynne, Traquair, not to name the far from secondary character of

the gallant Montrose. Gardiner, who patiently tramped over battlefields or

bicycled along out-of-the- way country lanes, as patiently as he read

through documents at the Record Office and pamphlets at the British Museum,

seemed to have entered into the life of the age as one who lived it;

and he saw with his own eyes the men who had lived and struggled and thought.

Sometimes, for a moment, it would seem as if he were blind to some entire

side of the life. He even once wrote of the age of Vandyke and Inigo Jones

and the masque-designers as an age in which grace and beauty were

forgotten.

He had, but again it was rarely, strange omissions. He

disposed—it is the most astounding thing in all his volumes—of

the political philosophy of Hobbes in little more than a page: he gave to

the most important book of the century less attention than to several

trumpery pamphlets of religious or political enthusiasts which had little

influence and few followers. But no man ever understood better the currents

and cross-currents of opinion in the age of which he wrote. Gardiner was

saturated with the pamphlet-literature of an age of pamphlets and, if it

might seem that there was only a phrase here or an epithet there to show

for all his labour, the knowledge gave him really the mastery of the

whole course of events and their causes, if not the whole course of thought.

And this is seen best of all when we remember how he knew and how he

estimated Puritanism—Puritanism at its best; for Puritanism after

all was the operative movement—not the stable force but the

movement—of the time. Wentworth could see nothing in Puritanism

but the dry unimaginative contentiousness of a Prynne

; some of Laud's

friends could see nothing but the root of all rebellion and disobedient

untractableness, and all schism and sauciness in the country, nay in the

Church itself.

Gardiner saw Puritanism in its strength as well as in

its weakness, and this he wrote of it.

It is the glory of Puritanism that it found its highest work in the strengthening of the will. To be abased in the abiding presence of the Divine Sufferer, and strengthened in the assurance of help from the risen Saviour, was the path which led the Puritan to victory over the temptations which so easily beset him. Then, as ever, it was not in the lap of ease and luxury that fortitude and endurance were most readily fostered, nor was it by culture and intelligence that the strongest natures were hardened. The spiritual and mental struggle through which the Puritan entered on his career of Divine service was more likely to be real with those who were already inured to a hard struggle with the physical conditions of the world, and whose minds were not distracted by too comprehensive knowledge of many-sided nature. The flame which flickered upwards burnt all the purer where the literature of the world, with its wisdom and its folly, found no entrance. It is not in the measured cadences of Milton, but in the homely allegory of the tinker of Elstow, that the Puritan gospel is most clearly revealed [History of the Great Civil War, i. 10.]

It is nothing to the purpose that these fine words are true of many of the Puritans' opponents: it is everything that Gardiner saw where the strength of Puritanism really lay. And, as was natural, he found the strength concentrated in Oliver Cromwell.

It is sad that the great and patient worker did not live to give his final

judgment on the character and achievements of the great Protector. He

anticipated such a judgment more than once, but the discoveries and

admissions—is it wrong to call them such?—of the later volumes,

the History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate,

prepared the way for

a less high-flown eulogy than that with which the Oxford lectures on

Cromwell's Place in History

concluded. Then in that remarkable course,

delivered, if I remember right, without a single note, with fluency unchecked

for a whole hour, and holding the audience spellbound by his historic

imagination and his moral fervour, Cromwell was compared to Shakespeare and

painted as the typical, almost the ideal, Englishman. As the years went on

it seemed certain to many of his readers that this verdict could not be

sustained. The verdict of Dr. Charles Firth is a sounder one. Towards that

verdict it can hardly be doubted that Dr. Gardiner would have tended. As he

finished his final survey he would, it is difficult to doubt, have been

compelled to admit that Cromwell was too much the representative of a party

to be a national hero in the fullest sense. He had begun, in the later

chapters he wrote, to emphasize the inconsistency of much of Oliver's

position, the consideration of material greatness never very far distant

from his spiritual enthusiasm,

the jerrymandering of elections in

the spirit of a pettifogging attorney,

the tolerant spirit that broke

down when it was found that the Royalists had religious ideals of their

own, [which] was a provocation which made it easy to deny them toleration

;

and last of all there is the admission, inevitable when the strange story of

the negotiations with Spain against France and of France against Spain is

fully revealed: It has been sometimes said that Oliver made England

respected in Europe. It would be more in accordance with truth to say that

he made her feared.

Still there was undoubtedly in the treatment of

the Protector a tendency to seek a favourable explanation of doubtful

points, to cast no critical eye on the diplomatic religion of the famous

letter to dear Robin

—a letter, as Dean Church called it,

which popular opinion would ascribe to a Jesuit

; to condone the

sending, by the champion of Protestantism, of English and Scots Protestants

to be slaves to Venetian papists; to dilute the tragic facts of the massacre

of Drogheda. But to say this is after all only to assert that the times

were a little too near his own, the principles for which men fought a

little too near his heart, for Gardiner, though he saw all the facts,

to see them always impartially.

And, in truth, fine though his perception of character, after long years

of intimate study, came to be, it was in grasp of principles, and in

dealing with the history as a whole, that Gardiner's chief strength lay.

It was for that reason that, he could turn aside for a moment from his

immediate task, marshal his facts, as it were in an instant, and scathe

in a brief review an ignorant or hasty adventurer, or pulverise an

ingenious argument as he did when he wrote What Gunpowder Plot was.

He was at home in the seventeenth century because he knew its principles as well as he knew its men.

Since his great book began to be widely read it has often been questioned

whether Gardiner's would be a permanent fame. Historical reputations, which

used to be easily made, are now more hardly won, but perish more rapidly.

Tried by Professor Bury's standard, the standard of that remarkable inaugural

lecture at Cambridge which marks an epoch in historical study, it is not

certain that the History of England, 1603-1655,

will survive, but

this at least is certain, that the Short History of the English People

will die before it, and that if it dies, The Norman Conquest,

and

even The Constitutional History of England,

will not be long in

following it to the tomb.

W. H. Hutton.

Source: Cornhill Magazine, December, 1908 (Vol. XV, No. 90.) pp. 785-796.

Samuel Rawson Gardiner (1829-1902), one of the great historical specialists of his time, gave in his career a supreme example of a life devoted to the realisation of a great idea. Born at Ropley in Hants, he was educated at Winchester School and at Christ Church, Oxford. Quitting Oxford in 1855, he married Isabella, youngest daughter of Edward Irving, the founder of the Apostolic Church, of which communion he became a member, and held high place in its hierarchy. In 1874 he was appointed Professor of History in King's College, London—a post which he held for fourteen years; and throughout the same period he acted as lecturer for the London Society for the Extension of University Teaching. In 1882 he received a pension of £150 from the Government of Mr Gladstone; and in 1884 All Souls College, Oxford, elected him to a Research Fellowship. On the death of Mr Froude in 1894 he was offered the Regius Professorship of History at Oxford; but, now in his sixty-fifth year, he declined the honour that he might devote himself to the great work of his life. He had honorary degrees from Oxford, Edinburgh, and Gottingen.

From the date of his leaving Oxford (1855) Gardiner addressed himself to

the task which he unremittingly pursued to the close of his

life—the history of England from the accession of James I. to the

Restoration. In 1865 the first instalment of the work appeared in two volumes,

and their successors followed at regular intervals till, in the last year of

his life, he was disabled by ill-health. A fragment of the third volume of

his History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate (1654-66) was posthumously

published in 1903. The great work, thus so nearly brought to completion,

is a monument of patient, exact, and disinterested labour ; but it was

likewise a labour of love which from first to last engaged the whole heart

and mind of its author. It was by natural affinity that Gardiner selected

the special period of English history of which he has produced such a minute

and exhaustive record. Of deep, though unobtrusive, religious feeling, he

was naturally attracted to a period when religion played so large a part

in the national development. His sympathies were with the Parliament

rather than with the Crown in the great controversy that cleft the English

nation in twain, but he was of too fair a mind and too genial a temper to

do injustice to any mode of thought or feeling, however alien to his own.

His estimates of the Royalists Strafford and Montrose are as generous as

his estimates of the Parliamentarians Pym and Hampden. Of Cromwell,

the dominating figure in his work, he has presented a portrait which in

many of its traits differs from that of Carlyle, yet (due deduction made

for the Carlylean emphasis) the lineaments presented in both portraits

are essentially the same. For Gardiner, Cromwell was the most

representative Englishman that ever lived

—typical of his

countrymen by his innate conservatism and

his statesmanship never determined by abstract theories, but by the

immediate perception of actual fact.

The greatness of Gardiner's work does not proceed from his power as a thinker

or from his skill as a literary artist; it was by his passion for truth and

accuracy, his candour and breadth of sympathy, his unwearying industry, that

he achieved a work which must ever hold its place among the chief historical

productions in English literature. In the sense in which the expression is

now employed, Gardiner was not, and did not desire to be, a

scientific historian.

He did not conceive it to be the duty of the

historian to efface

himself in the presentation of his materials, nor to eschew all expression

of his own opinion on the events and actions he has to narrate. Everywhere

he frankly pronounces his judgments, whether of condemnation or approval;

and in so doing he held that he was discharging not the least important

function of the historian. In his conception, if history was not directly

didactic, the writing of it is a vain labour; and the true scientific

historian is he who most conscientiously seeks to ascertain and present

the lessons which the past has to offer.

P. Hume Brown

Source: Chambers Cyclopædia of Literature, London, 1903. Vol. III. p. 631

GARDINER, SAMUEL RAWSON (1829-1902), English historian, son of Rawson Boddam Gardiner, was born near Alresford, Hants, on the 4th of March 1829. He was educated at Winchester and Christ Church, Oxford, where he obtained a first class in literæ humaniores. He was subsequently elected to fellowships at All Souls (1884) and Merton (1892). For some years he was professor of modern history at King's College, London, and devoted his life to historical work. He is the historian of the Puritan revolution, and has written its history in a series of volumes, originally published under different titles, beginning with the accession of James I.; the seventeenth (the third volume of the History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate) appeared in 1901. This was completed in two volumes by C. H. Firth as The Last Years of the Protectorate (1909). The series is History of England from the Accession of James I. to the Outbreak of the Civil War, 1603-1642 (10 vols.); History of the Great Civil War, 1642-1640 (4 vols.); and History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate, 1649-1660. His treatment is exhaustive and philosophical, taking in, along with political and constitutional history, the changes in religion, thought and sentiment during his period, their causes and their tendencies. Of the original authorities on which his work is founded many of great value exist only in manuscript, and his researches in public and private collections of manuscripts at home, and in the archives of Simancas, Venice, Rome, Brussels and Paris, were indefatigable and fruitful. His accuracy is universally acknowledged. He was perhaps drawn to the Puritan period by the fact of his descent from Cromwell and Ireton, but he has certainly written of it with no other purpose than to set forth the truth. In his judgments of men and their actions he is unbiassed, and his appreciations of character exhibit a remarkable fineness of perception and a broad sympathy. Among many proofs of these qualities it will be enough to refer to what he says of the characters of James I., Bacon, Laud, Strafford and Cromwell. On constitutional matters he writes with an insight to be attained only by the study of political philosophy, discussing in a masterly fashion the dreams of idealists and the schemes of government proposed by statesmen. Throughout his work he gives a prominent place to everything which illustrates human progress in moral and religious, as well as political conceptions, and specially to the rise and development of the idea of religious toleration, finding his authorities not only in the words and actions of men of mark, but in the writings of more or less obscure pamphleteers, whose essays indicate currents in the tide of public opinion. His record of the relations between England and other states proves his thorough knowledge of contemporary European history, and is rendered specially valuable by his researches among manuscript sources which have enabled him to expound for the first time some intricate pieces of diplomacy.

Gardiner's work is long and minute; the fifty-seven years

which it covers are a period of exceptional importance in many

directions, and the actions and characters of the principal persons

in it demand careful analysis. He is perhaps apt to attach an

exaggerated importance to some of the authorities which he was

the first to bring to light, to see a general tendency in what may

only be the expression of an individual eccentricity, to rely too

much on ambassadors' reports which may have. been written for

some special end, to enter too fully into the details of diplomatic

correspondence. In any case the length of his work is not the

result of verbiage or repetitions. His style is clear, absolutely

unadorned, and somewhat lacking in force; he appeals constantly

to the intellect rather than to the emotions, and is seldom

picturesque, though in describing a few famous scenes, such as the

execution of Charles I., he writes with pathos and dignity. The

minuteness of his narrative detracts from its interest; though

his arrangement is generally good, here and there the reader

finds the thread of a subject broken by the intrusion of incidents

not immediately connected with it, and does not pick it up again

without an effort. And Gardiner has the defects of his supreme

qualities, of his fairness and critical ability as a judge of character;

his work lacks enthusiasm, and leaves the reader cold and unmoved.

Yet, apart from its sterling excellence, it is not without

beauties, for it is marked by loftiness of thought, a love of purity

and truth, and refinement in taste and feeling. He wrote other

books, mostly on the same period, but his great history is that by

which his name will live. It is a worthy result of a life of unremitting

labour, a splendid monument of historical scholarship.

His position as an historian was formally acknowledged: in 1862

he was given a civil list pension of £150 per annum, in recognition

of his valuable contributions to the history of England

;

he was honorary D.C.L. of Oxford, LL.D. of Edinburgh, and

Ph.D. of Gottingen, and honorary student of Christ Church,

Oxford; and in 1894 he declined the appointment of regius

professor of modern history at Oxford, lest its duties should

interfere with the accomplishment of his history. He died on

the 24th of February 1902.

Among the more noteworthy of Gardiner's separate works are: Prince Charles and the Spanish Marriage (2 vols., London, 1869); Constitutional Documents of the Puritan Revolution, 1625-1660 (1st ed., Oxford, 1889; 2nd ed., Oxford, 1899); Oliver Cromwell (London, 1901); What Gunpowder Plot was (London, 1897); Outline of English History (1st ed., London, 1887; 2nd ed., London, 1896); and Student's History of England (2 vols., 1st ed., London, 1890- 1891; 2nd ed., London, 1891-1892). He edited collections of papers for the Camden Society, and from 1891 was editor of the English Historical Review.

Rev. William Hunt, (President of the Royal Historical Society.)

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th ed., Vol. 11, p. 460.

… When

I explained to

Dr. Garnett my errand, an elaborate investigation of

an historic figure [Henry Vane, the younger], said he: You must know

Samuel Rawson Gardiner, the best living authority for the period of the

English Civil War. Now Dr. Gardiner is peculiar. His great history of that

period as yet takes in nothing later than 1642. Up to that date he will have

all the information and help you generously. Of the time beyond that date

he will have nothing to say, be mute as a dumb man. He has not finished his

investigations and has a morbid caution about making any suggestion based

on incomplete data.

A day or two afterward I was in the Public Record Office in Fetter Lane, the roomy fire-proof structure which holds the archives of England. You sit in the Search Room, a most interesting place. Rolls and dusty tomes lie heaped about you, the attendants go back and forth with long strips of parchment knotted together by thongs, hanging down to the floor before and behind, written over by the fingers of scribes in the mediaeval days and sometimes in the Dark Ages. The past becomes very real to you as you scan Domes Day Book which once was constantly under the eye of William the Conqueror, or the documents of kings who reigned before the Plantagenets. As I sat busy with some original letters of Henry Vane, written by him when a boy in Germany in the heart of the Thirty Tears' War, a vigorous brown-haired man came up to me with a pleasant smile and introduced himself as Samuel Rawson Gardiner. Dr. Garnett had told him about me and about my especial quest, and with rare kindness, he offered to give me hints. It was for me a fortunate encounter, for no other man knew, as Gardiner did, the ground I desired to cover. He put into my hands old books, unprinted diaries, scraps of paper inscribed by great figures in historic moments, the solid sources, and also the waifs and strays from which proper history must be built up. He would look in upon me time after time in the Search Room; in the Reading Room of the British Museum we sat side by side under the great dome. We were working in the same field and the experienced master passed over to the neophyte the yellow papers and mildewed volumes in which he was digging, with suggestions as to how I might get out of the chaff the wheat that I wanted. He invited me to his home at Bromley in Kent, where he allowed me to read the proofs of the volume in his own great series which was just then in press. It related to matters that were vital to my purpose and I had the rare pleasure of reading a masterly work and seeing how the workman built, inserting into his draft countless marginal emendations, the application of sober second thought to the original conception. I spent the best part of the night in review and it was for me a training well worth the sacrifice of sleep. In the pleasant July afternoon we sat down to tea in the little shaded garden where I met the son and daughter of my host and also Mrs. Gardiner, an accomplished writer and his associate in his labours. The interval between tea and dinner we filled up with a long walk over the fields of Kent during which appeared the social side of the man. He told me with modesty that he was descended from Cromwell through Ireton, and the vigour of his stride, with which I found it sometimes hard to keep up, made it plain that he was of stalwart stock and might have marched with the Ironsides. A day or two later he bade me good-bye; he and his wife departing for the continent for a long bicycle tour. The indefatigable scholar was no less capable in the fields and on the high road than in alcoves and the Search Room.

Source: Hosmer, James Kendall, A Last Leaf, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1912.