|

| Image from Wikipedia. |

|

| Image from Wikipedia. |

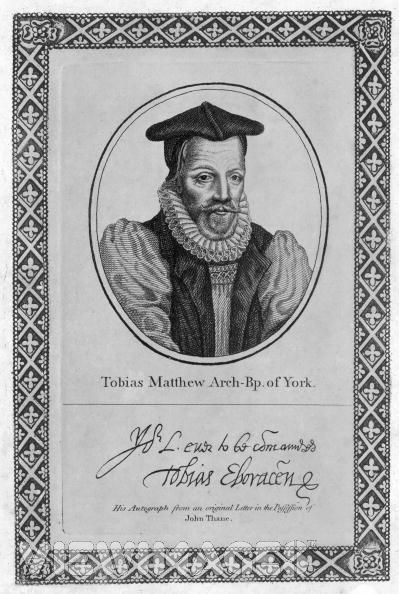

MATTHEW, TOBIE or TOBIAS (1546-1628),

archbishop of York, was the

son of John Matthew of Ross, Herefordshire,

and his wife Eleanor Crofton of Ludlow. He was born at Bristol in 1546, and

gave many books to his native city when

archbishop (Godwin, De Præsulibus Angliæ,

1616). He received his early education at

Wells and matriculated at Oxford as a probationer

of University College in 1559. He

graduated B.A. in February 1563/4. In

February 1564/5 he was a member of Christ

Church, and he proceeded M.A. in July 1566,

being then student of that house. He was

ordained in the same year, at which time

he was much respected for his great learning,

eloquence, sweet conversation, friendly

disposition, and the sharpness of his wit

(Wood, Athenæ Oxonienses). When Queen

Elizabeth visited the university in the same

year he took part in a disputation in philosophy

before her in St. Mary's Church on

3 Sept., arguing in favour of an elective as

against an hereditary monarchy. When the :

queen left Christ Church on her departure

from Oxford, he bade her farewell in an eloquent

oration (Elizabethan Oxford, Oxford

Historical Society). His handsome presence

and his ready wit attracted the queen's notice.

He was one of a proper person (such people,

cæteris paribus and sometimes cæteris imparibus,

were preferred by the queen) and an

excellent Preacher

(Fuller, Church History,

p. 133). The queen continued her

favour to him throughout her life (Thoresby,

Vicaria Leodiensis, gives many instances),

and was equally kind to his wife, on whom

she bestowed a fragment of an unicorn's

horn.

On 2 Nov. 1569 he was unanimously

elected public orator of the university, and

held the office till August 1572. In 1570

he was appointed a canon of Christ Church,

on 28 Nov. 1572 archdeacon of Bath, on

15 May 1572 prebendary of Teynton Regis in

the cathedral of Salisbury, and being much

famed for his admirable way of preaching he

was made one of the queen's chaplains in

ordinary

(Wood, Athenæ Oxon.)

On 17 July

1572 he was elected president of St. John's

College, which had then an intimate connection

with Christ Church. He was the fifth

president since the foundation seventeen

years before, and he had to struggle with the

difficulties of a poor and divided college. In

1573 he endeavoured, on the score of poverty,

to win release from the annual obligation

to elect scholars from Merchant Taylors'

School (Wilson, History of Merchant Taylors'

School}. In 1576 he was appointed dean

of Christ Church, and resigned the headship

of St. John's on 8 May 1577. He took the

degree of B.D. 10 Dec. 1573, and D.D. June

1574. On 14 July 1579 he was nominated

vice-chancellor of the university by Robert

Dudley, earl of Leicester, then chancellor.

When Campion published his Decem Rationes

in 1581, Matthew's was the first answer from Oxford. In a Latin sermon before

the university, 9 Oct. 1581, he defended the

Reformation, appealing chiefly to the teaching

of Christ and primitive Christianity, and

refraining from either quoting or defending

Luther. In June 1583 he became precentor

of Salisbury, but resigned in the following

February. He was installed as dean of Durham

31 Aug. 1583, and resigned the deanery

of Christ Church early in 1584. He was inducted

as vicar of Bishop's Wearmouth on

28 May 1590.

While dean of Durham, Matthew acted as

a political agent of the government in the

north, and was a vigorous pursuer of recusants.

Through him the queen's advisers

frequently received information on the condition

of Scotland (a court and kingdom as

full of welters and uncertainties as the moon

is of changes,

Tobie Matthew to Walsingham,

15 Jan. 1593, Cal. State Papers}. He

was none the less active as an orator, and his

services as preacher were eagerly sought all

over the county palatine. Yet for all his

pains in preaching he neglected not his proper

episcopal acts of visitation, confirmation, ordination,

&c. … he confirmed sometimes

five hundred, sometimes a thousand at a time;

yea, so many that he hath been forced to betake

himself to his bed for refreshment. At

Hartlepool he was forced to confirm in the

churchyard.

In 1595 he was promoted to the

bishopric of Durham. A letter of his successor

in the deanery to Cecil (16 Jan. 1597 ib.)gives

a graphic picture of the condition of the great

northern diocese at the time. In the bishopric

five hundred ploughs had decayed within fifty

years. Of eight thousand acres lately in

tillage not eight score were then tilled, and

the people were driven into the coast towns.

In Northumberland great villages were dispeopled,

and there was no man to withstand

the enemy's attack. The misery had arisen

through decay of tillage.

Amid the confusion recusancy held up its head. Matthew sat in the court of high commission and examined the offenders, but they were obstinate. The remedies suggested for the condition of Northumberland (June 1602, ib.) show the difficulties against which he had to contend. The bishop, it is proposed in this paper, should compel his incumbents to be resident and preach, and the queen's farmers of taxes who hold Hexham, Holy Island, Bamborough, and Tynemouth, and leave churches either wholly unprovided, or supplied with mean curates, ought to be forced to support preachers. The bishop seems gradually to have brought about an improvement; he was most energetic in discharge of his duties, and constantly sent up lists of recusants and examinations of suspected persons. His services were recognised by James I no less than by his predecessor; he took a prominent part in the Hampton Court conference, and preached at the close before the king, who greatly admired his sermons (cf. Strype, Whitgift, App. pp. 236-8).

On 18 April 1606 he was appointed archbishop

of York, on the death of Dr. Matthew

Hutton, whom he had succeeded also at Durham.

In the primacy his political activity increased.

He was named on the commission

for examining and determining all controversies

in the north

(21 July 1609, ib.) He

was given the custody of the Lady Arabella

Stuart, and it was from his house

that she escaped in June 1611. He preached

the sermon on the opening of parliament in

1614. In the same year, when the lords refused

to meet the commons in conference on

the impositions, and sixteen bishops voted

in the majority, Matthew alone voted for

conferring with the lower house. If the letter

in Cabala

is genuine (see below), this was

not the only occasion on which he opposed

the royal policy. During his last years he

retired from political life, and was excused

attendance at parliament, 1624-6, on account

of his age and infirmities. In 1624 he gave

up York House to the king for Buckingham,

in exchange for certain Yorkshire manors.

As early as 1607 rumours of his death

were abroad (J. Chamberlain to Dudley Carleton,

ib. 30 Dec. 1607), and he was supposed

to encourage them. He died yearly,

says

Fuller (Church History, p. 133), in report,

and I doubt not but that in the Apostle's

sense he died daily in his mortifying meditations.

In 1616 one of these reports caused

considerable mirth at the expense of the

avaricious archbishop of Spalatro, who applied

to the king for the see which he supposed

to be vacant (Gardiner, Hist. of Engl.

iv. 285). Matthew died on 29 March 1628,

and was buried in York Minster, where his

tomb stands (the effigy now separate) in the

south side of the presbytery.

Matthew, though renowned in his day as

a preacher and divine, was a statesman quite

as much as a prelate. The advisers of Elizabeth

and James felt that they could rely upon

him to watch and guard the northern shires.

None the less was he a diligent bishop and

a pious man. He had an admirable talent

for preaching, which he never suffered to lie

idle, but used to go from one town to another

to preach to crowded audiences. He kept

an exact account of the sermons which he

preached after he was preferred; by which it

appears that he preached, when dean of Durham,

721; when bishop of that diocese, 550;

when archbishop of York, 721; in all, 1992

(Granger, Biographical History, i. 342). He

was noted for his humour. He was of a

cheerful spirit,

says Fuller, yet without any

trespass on episcopal gravity, there lying a

real distinction between facetiousness and

nugacity. None could condemn him for his

pleasant wit, though often he would condemn

himself, as so habited therein he could as well

be as not be merry, and not take up an innocent

jest as it lay in the way of his discourse

(Church History, p. 133).

He married Frances, daughter of William

Barlow (d. 1568), sometime bishop of

Chichester, and widow of Matthew Parker,

second son of the archbishop. She was a

prudent and a provident matron

(ib.), gave

his library of over three thousand volumes

to the cathedral of York, and is memorable

likewise for having a bishop to her father, an

archbishop to her father-in-law, four bishops

to her brethren, and an archbishop to her

husband

(Camden, Britannia). She died

10 May 1629. Their brilliant son, Sir Tobie,

was a great trouble to his father. Two

younger sons were named John and Samuel,

and there were two daughters (Hunter,

Chorus Vatum, Addit. MS. 24490, f. 234).

His portrait in the hall of Christ Church, Oxford, shows him as a small, meagre man, with moustache and beard turning grey.

Matthew published Piissimi et eminentissimi

viri Tobias Matthew Archiepiscopi

olim Eboracensis concio apologetica adversus

Campianum. Oxoniæ excudebat Leonardus

Lichfield impensis Ed. Forrest an. Dom.

1638.

There is a manuscript in late sixteenth-century

hand in the Bodleian. The

sermon seems to have been largely circulated

in manuscript, though it was not printed till

ten years after the archbishop's death. Matthew

is also credited with A Letter to

James I

(Cabala, i. 108). This is a severe

indictment of the king's proposed toleration

and of the prince's journey into Spain. The

writer declares that the king was taking to

himself a liberty to throw down the laws

of the land at pleasure, and threatens divine

judgments. The letter is unsigned and undated,

and, in default of evidence of authorship,

it seems improbable that Matthew was

the writer. Thoresby attributes it to George

Abbot.

I have been informed that he had several

things lying by him worthy of the press, but

what became of them after his death I know

not, nor anything to the contrary, but that

they came into the hands of his son, Sir

Tobie

(Wood, Athenæ Oxon.}

[For the degrees and university offices held by Matthew the Reg. of Univ. of Oxford, ed. Boase and Clark (Oxford Hist. Soc.) For later life : St. John's College MSS.; Wood's Athenæ Oxon.; Fuller's Church Hist.; Godwin, De Praesulibus Angliæ; H. B. Wilson's Hist, of Merchant Taylors' School; Granger's Biog. Hist.; Camden's Britannia; Le Neve's Lives of Bishops since the Reformation; Thoresby's Vicaria Leodiensis, pp. 155 sq. (largely from the archbishop's manuscript diary). The Calendars of State Papers afford many illustrations of the archbishop's political and private life.]

W. H. H. [The Rev. W. H. Hutton.]

Source: Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 37, pp. 61-63